The Great Architect

Sinan

The Life of The Great Architect Sinan

The information we have on the life and personality of Sinan is

rather limited. We have neither manuscripts nor theoretical

expositions written by him. If there are any sketches or plans

anonymously drawn by him as was the practice at the time, they have

not reached us. The information we have on the life and personality of Sinan is

rather limited. We have neither manuscripts nor theoretical

expositions written by him. If there are any sketches or plans

anonymously drawn by him as was the practice at the time, they have

not reached us.

Sinan was a Christian born in Ağırnas village, in Kayseri province.

We do not know the precise date of his birth, but it must have been

somewhere between 1494 and 1499. He was recruited in 1512 or 1513 by

the "devşirme" to be enrolled in the Janissary Corps. It was the

first time a child was recruited for that purpose in the Kayseri

region. Sinan must have been between fourteen and eighteen years old

at the time. Some of the Christian children who were recruited into

the Devşirme system became part of the Janissary Corps, while others

were sent to the palace after receiving an education, and served the

government. Sinan was trained in the Acemi Ocağı, a sort of palace

school, where he learnt carpentry and worked on building sites.

During the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, he became a

member of the Janissary Corps in the Belgrade and Rhodes campaigns

in 1521 and 1522 resprectively, after which he was given the rank of

"Atlısekban." He was promoted to the rank of "Yayabaşı" after the

Mohacs battle, and later to that of "Kapıyayabaşı." He participated

in the German campaign between 1529-32 as a "Zemberekçibaşı," as

well as in the Iran and Baghdad campaigns (the Irakeyn campaign) in

1534-1535. He built three fully equipped and armed galleys for the

crossing of Lake Van. As a result of this and his other achievements

as an engineer in previous campaigns, he was promoted to the rank of

"Haseki" in the sultan's bodyguard. After the Puglia and Korfu

campaigns (1537), he won wide acclaim for the bridge he built in a

very short time during the Moldavian campaign. During this campaign,

the chief architect,Acem Alisi died, upon which the Sadrazam (Prime

Minister) Lütfi Paşa appointed Sinan, then a "Subaşı"

(Superintendent), to the post of "Mimarbaşı" (Chief Architect).

Sinan's previous achievements in civil architecture played an

important role in this promotion. When recalling this event, Sinan

says he was sad to leave the army but happy to have the opportunity

to accomplish other important things such as building mosques. Sinan

was already of a mature age when he became chief architect. He had

seen monuments and works of different cultures during the campaigns

in which he participated both in the west and in the east. He had

been faced with problems that needed rapid solutions, and the army

had given him discipline, self-control and organizational skills.

The training and experience he had must have helped him develop his

skills in designing and in administration. Sinan's career as chief

architect lasted for some fifty years.

According to the documents which list his works, he designed,

supervised, built or restored as many as 400 buildings. But if we

consider the fact that he was in charge of the Imperial Corps of

Architects and that Ottoman territory was vast , it becomes

difficult to conceive that all these works were personally produced

by Sinan. However, with the exception of those built towards the end

of his life, the buildings erected in Istanbul are assumed to be

his. Moreover most of Sinan's smaller buildings have not survived in

their original form, however the works Sinan had created in Istanbul

are sufficient to demonstrate his enormous contribution to Turkish

architecture.

Architects do not seem to have held an important place in the

Ottoman State protocol. At a time when the empire was very powerful,

Sinan designed buildings for three successive sultans, as well as

for numerous palace notables, a sure sign that he enjoyed great

popularity and was much appreciated as an architect. The fact that

Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent would have asked Sinan to lead the

opening ceremony for the Süleymaniye Mosque even though he had had

it built in his own name, is another unmistakable indication of such

appreciation and esteem. According to the charter of the vakıf he

founded in 1563, Sinan was able to acquire a fortune including 18

mansions, 38 shops, 9 houses, land, mills, small mosques and

schools. In 1583 he made a pilgrimage to Mecca, and had his life

story and a list of his works recorded by a poet friend. According

to the inscription on his tomb, which is situated next to the

Süleymaniye Mosque, Sinan died in 1588.

Sinan obviously had a perfect understanding of the topography of

Istanbul, the city in which he designed so many buildings, and he

was able to make the most of this knowledge. It is probably not

wrong to suppose that he must have visited and studied the

architecture of Saint Sophia very often.

At that time, Istanbul was a developed city, which was adorned with

hundreds of new buildings, some of which were ordered built by the

most powerful Ottoman Sultans, such as Fatih Sultan Mehmet and

Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, as well as their relatives and high

ranking state officials. All the revenues of the Empire flowed into

the city where the best artisans and artists gathered. Sinan was at

the head of an organisation in charge of the vast territories of the

Empire, with numerous buildings being built in such places

stretching from Bosnia to Bagdad and from Crimea to Yemen. Sinan had

had the opportunity to travel to many countries, where he studied

and closely analyzed much of the architecture. Besides his sense of

space, he had acquired vast knowledge regarding buttressing systems.

That he should have designed the Şehzade Mosque only two years after

being named chief architect is an indication not only of his

architectural skills, but also of his vast experience and

perception. Throughout his life, Sinan constantly studied, carried

out experiments and sought answers to problems in topography, space,

mass and buttresses. In doing so, he provided diverse and highly

elaborate solutions, which make him the great master of Ottoman, and

even Islamic architecture. Top

The Works of Sinan

According to the sources available on Sinan's career, he produced

more than four hundred works. It may be safer to say that these

works were built or restored during his lifetime. We shall not

attempt to describe each and every one of Sinan's works but rather

focus on the most important ones, as well as those which are most

representative of his art.

Religious complexes (Külliyes) had diverse public service functions,

the most important of which was religious. The main building of the

complex was the mosque, followed by the medrese or theological

seminary. The complex would usually also include the following: a

soup kitchen or refectory, guesthouse, hospital, school, public

bath, fountain, water distribution kiosk and shops. The tomb of the

person who had ordered the project would generally be situated

within the complex. Külliyes situated on the main caravan routes

would include in addition to the kervansaray, a prayer hall, hamam,

soup kitchen, shops and stables. The külliyes were powerful social

poles, and the fact that they were conceived as vakıfs ensured their

continuity. The activities carried out in these complexes

considerably stimulated the urban development of the areas in which

they were built. Therefore, many külliyes were built in newly

settled areas in order to help in their development. The duties and

rights of each külliye were specified in detail in the foundation's

charter and the people in charge of the vakıf implemented the

regulations in the charter.

The külliyes designed by Sinan were exquisitely conceived, be it

from the standpoint of the site chosen, integration with rough

terrain, or as regards harmony achieved with the city's general

skyline. Most of Sinans structures are situated on hilltops or

along the seashore where they can be easily seen. They strike the

eye as one approaches the city, constituting an inseparable part of

its silhouette. The choice of the site is not only related to the

Külliye's appearance from afar, but also to the view one has of the

city from inside the complex, a view enhanced with the spectacle of

the sea offered by the shores of the Bosphorus and Golden Horn.

Sinan was especially skilled in adopting his design to sloping

terrains. Solving such problems seems to have been like some sort of

entertaining crossword puzzle for him. The buildings which

constitute the külliye are very skilfully situated at levels

corresponding to their function and importance. The final result is

a well graded complex offering a fine appearance visible from afar,

and forming an organic whole dominated by the mosque. Top

Some of The

Masterpieces of Architect Sinan

Suleymaniye

Mosque

Mihrimah

Sultan Mosque

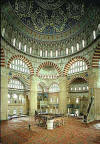

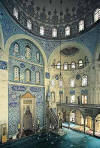

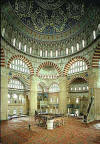

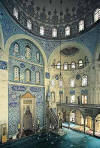

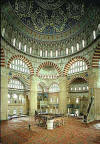

Inner views of Selimiye Mosque/Edirne

Haseki Hamami (Turkish Bath)

Sokollu (Selim II) Kulliyesi/Hatay Payas (Kulliye is complex of

buildings adjacent to a mosque).

Sokollu Mosque/Kadirga/Istanbul

Mihrimah Sultan Mosque/Uskudar

Top

Some of His

Other Works

Haseki Külliyesi

Şehzade Külliyesi

Süleymaniye Külliyesi

Atik Valide Külliyesi, Üsküdar

Sokollu Külliyesi, Lüleburgaz

Süleymaniye Külliyesi, Şam

Sokollu (Selim II) Külliyesi, Hatay Payas

Camiler (mosques)

Dört Dayanaklı - Tek Kubbeli Camiler (with

unique dome)

Hadım İbrahim Paşa Camisi, Silivrikapı

Mihrimah Sultan Camisi, Edirnekapı

Zal Mahmut Paşa Camisi, Eyüp

Dört Dayanaklı - Yarım Kubbeli Camiler (with

half dome)

Mihrimah Sultan Camisi, Üsküdar

Şehzade Camisi

Sülaymaniye Camisi

Kılıç Ali Paşa Camisi

Altı Dayanaklı Camiler

Sinan Paşa Camisi, Beşiktaş

Kara Ahmet Paşa Camisi, Topkapı

Molla Çelebi Camisi, Fındıklı

Semiz Ali Paşa Camisi, Babaeski

Atik Valide Camisi, Üsküdar

Sokollu Camisi, Kadırga

Top

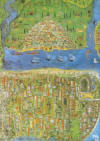

The Ottoman Empire during the Time of Sinan

The Ottoman Empire was established in 1299, and it grew steadily,

putting an end to the Byzantine Empire in 1453. It reached its peak

by the end of the 16th century. The Empire included a diversity of

cultures, which were preserved locally, while its general character

remained eastern and Ottoman. After its conquest, Istanbul became

the artistic and cultural centre of the empire, diffusing its

influence across its various provinces in proportion to the

relations it maintained with them.

Eastern influences, especially those brought back from the campaigns

waged in the East by Sultan Selim I and his successor Süleyman the

Magnificent, also known as Kanuni (Law-Giver)- were integrated into

the vast and mature Ottoman culture, as had previously been the case

with Byzantine architecture. The most brilliant period of Ottoman

civilisation was during the 16th and 17th centuries, during which

time the most famous names achieved great feats in fields of

science, administration and in the arts.

This was due in great part to the empire's economic power, but also

to a well organised and stable administration, the prevalence of

justice and fairness, as well as a rational world view.

In Sinan's time, the Islamic institution of the vakıf or waqf, a

kind pf pious charitable foundation, was highly developed. It was

through the establishment of such foundations and in a charitable

spirit that sultans and members of their families, as well as

viziers (ministers), and pashas (generals) contributed funds for the

establishment of many public works. The wealthy also followed their

examples. We can say that practically all the architectural works of

that time were built by vakıfs, but it was still the State which

provided the revenues for the donors.

Indeed many important State resources were entrusted to prominent

people through the institution of the "mülk". And this made it

possible for viziers such as Rüstem Paşa and Sokullu Mehmet Paşa (we

shall henceforth use Turkish spelling for Turkish names) and

princesses of the Imperial Harem, such as Hürrem Sultan and Mihrimah

Sultan (the word Sultan placed after a woman's name means princess),

to order numerous vakıf projects.

During the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent a most active

period was witnessed in the Empire in terms of the construction of

public works, and Sinan was most fortunate to have the post of chief

architect at a time when resources were so abundant. The vakıf

system not only permitted the building of such works, it also

ensured their maintenance, which made it possible for them to

survive until this day. Funds for their maintenance were provided by

the revenues obtained from shops, commercial buildings and

kervansarays (hostels for merchants and travellers), hamams (public

baths), bedestens or mills, all constructed next to monuments built

by donations. The administration of these revenues was entrusted to

the vakıfs. The establishment of vakıfs was always encouraged, and

many facilities were provided for that purpose. The founder of the

vakıf could specify how it was to be used through its administrative

statutes or vakfiye. Such freedom of choice brought a significant

plurality to Ottoman social and cultural life. As for other works

which were directly undertaken by the State, they consisted of

military establishments, roads and bridges, as well as palaces and

buildings.

Ottoman Sultans of the 16th century were not only patrons of the

arts but were also directly involved in their administration. They

established workshops which specialized in all kinds of crafts.

Artists and artisans of the Palace (the Ehl-i Hiref), ranging from

painters to calligraphers, from carpenters to jewellers, were

trained at these establishments, where they were then able to

contribute to the art of the Empire. The wages earned by these

artists were higher than those of civil servants working at the

Palace. This explains why architectural works were built with such

care. Top

The Imperial Corps of Architects

Ottoman documents reveal that there was a special architectural

institution attached to the palace called the Hassa Mimarlar Ocağı

(Imperial Corps of Architects). The date of the founding of this

institution is not clear but we do know that it was already in

existence before 1525. It was linked to the Şehremini (an individual

responsible for the financing, purchasing and administrative

activities related to the construction of buildings). The Hassa

Chief architect was in charge of its administration. The first chief

architect is believed to have been Acem Alisi (Alaüddin). The chief

architect had as his assistants the water supply director, the chief

of apprentices, the chief limeworker, the warehouse director, the

first secretary of the warehouse, the first architect, the deputy

architect, the director of repairs, and many master architects,

qualified builders, foreman and artisans, as well as officers in

charge of monitoring their activities. The institution was in charge

of practically everything related to the empire's civil engineering,

architecture and urban development activities: water supply,

sewerage system, roads and pavements, building regulations, permits

and their control, as well as fire prevention, the activities of

architects, foremen and superintendents and their wages, the

standardisation of building materials and their quality and price

control.

It was also in

charge of designing, erecting, maintaining and repairing buildings

belonging to the imperial family, high-ranking state officials, and

of appointing architects, foremen and superintendents for these

tasks. In addition, it was responsible for the building of bridges,

forts and other military works in times of war. Finally, it

functioned as an educational institution, being in charge of the

training of the most talented youths among those recruited by the "devşirme"

(levy of Christian children for the Jannisary Corps and other State

services).

The plans for building projects were first in the form of sketches

or models and then they were submitted to the palace together with

their cost estimates. Before construction began, someone was

appointed to be in charge of the building, who would also be

responsible for the building materials and workers, and who would

regularly note down the expenses incurred. For important projects,

the palace would be directly approached for the procurement of

materials and staff. In the provinces, the "kadıs", who functioned

both as judges and mayors, would inform the palace of their building

requirements and the latter would then give orders to the chief

architect. In the construction of imperial buildings, young devşirme

recruits, palace artisans (Ehl-i Hiref), hired laborers and

foremasters worked along with prisoners of war and convicts. Both

Muslims and Christians would be employed. If necessary, architects

would be sent to different provinces and sometimes abroad. The

Muslim rulers of India are known to have asked the Ottoman Sultans

to send them architects, and some of Sinan's students were indeed

sent there.

It is believed that the Imperial Corps of Architects became masters

during Sinan's time when it was restructured in order to handle the

then frantic building activity. The institution lasted for some 350

years, until it was integrated into the municipality in 1831.

Top

Ottoman Architecture Prior to Sinan

In order to get a better understanding of Sinan's architectural

achievements, we must dwell briefly on the architectural

developments that preceded them. Sinan's greatest contribution lies

in his innovations regarding the use of the dome. With the exception

of certain tombs, domes did not cover the whole area of buildings in

the Islamic world, rather they served to enhance buildings. The

Ottomans virtually identified their mosques with domes, trying out

every possible variant of the form. The role of Saint Sophia in this

context cannot be denied. The function of the dome was moreover not

limited to covering a given area, it became a key element in the

design of a mosque.

Single, multiple, plural-based or multi-functional inverted T-shaped

domed mosques and their domed tombs, departing from the old kümbet

form, were already a typical Ottoman style at the time when Bursa

was the first capital of the empire (1326), along with domed

medreses (theological seminaries), and domed hamams.

The Bursa style continued for some time after the city of Edirne was

proclaimed the second capital of the Empire in 1368, but the Üç

Şerefeli Mosque, built in Edirne by Murad II in 1447, is considered

an innovation in the design of mosques because it introduced a plan

which was to be amply developed later.

Innovative features like the hexagonal structure supporting its

dome, its porticoed courtyard and its four minarets, do indeed

impart a character to the mosque not typical of the period.

After the conquest of Istanbul (1453), the Saint Sophia Basilica,

which was much admired by the Ottomans, became a focus of interest

for Turkish architects, who practically idolized it. The Fatih

(Conqueror) Külliye (a religious complex) was completed in 1471

under the reign of Mehmet II. With its sixteen medreses, its

location and composition, this monumental complex put a Turkish

stamp on the city. A semidome was added to the main dome of the

original Fatih mosque, probably being influenced by the architecture

of Saint Sophia, which brought the concept into Ottoman

architecture. The old Fatih mosque was still standing in Sinan's

time. It was to be destroyed in the 1776 earthquake. Also

interesting is the Beyazid II Külliye in Edirne (1488), with

pendentives supporting a 20m diameter dome and the design of its

hospital. The interior of the mosque is dominated by a single dome.

The side walls have windows and the dome supports are almost

unnoticeable. This was the prototype for the Mihrimah Mosque in

Edirnekapı, which Sinan was to build some 80 years later. The

Beyazid II Mosque in Istanbul (1506) is an improved version of the

old Fatih Mosque. The influence of Saint Sophia may also be felt

here, but must not be considered to be a simple copy.

The works mentioned above indicate that Ottoman architecture was

already developed by the time Sinan appeared. Top

References and External Links

- Sinan, The Architect and his Works, by

Prof. Dr. Reha Günay, translated by Ali Ottoman

-

Turkish Art &

Architecture

-

Architect Sinan, Wikipedia

(English)

-

Mimar

Sinan, Wikipedia (French)

-

Sinan'a Saygi

TransAnatolie Tour

|

The information we have on the life and personality of Sinan is

rather limited. We have neither manuscripts nor theoretical

expositions written by him. If there are any sketches or plans

anonymously drawn by him as was the practice at the time, they have

not reached us.

The information we have on the life and personality of Sinan is

rather limited. We have neither manuscripts nor theoretical

expositions written by him. If there are any sketches or plans

anonymously drawn by him as was the practice at the time, they have

not reached us.