The Ultimate Optimization Problem: How to Best

Use Every Square Meter of the Earth's Surface

Lucas Joppa, founder of Microsoft's AI for Earth program, is taking an

engineering approach to environmental issues.

Lucas Joppa thinks big. Even while gazing down into his cup of tea in

his modest office on Microsoft’s campus in Redmond, Washington, he seems

to see the entire planet bobbing in there like a spherical tea bag.

As Microsoft’s first chief environmental officer, Joppa came up with the

company’s AI for Earth program, a five-year effort that’s spending US

$50 million on AI-powered solutions to global environmental challenges.

The program is not just about specific deliverables, though. It’s also

about mindset, Joppa told IEEE Spectrum in an interview in July. “It’s a

plea for people to think about the Earth in the same way they think

about the technologies they’re developing,” he says. “You start with an

objective. So what’s our objective function for Earth?” (In computer

science, an objective function describes the parameter or parameters you

are trying to maximize or minimize for optimal results.)

AI for Earth launched in December 2017, and Joppa’s team has since given

grants to more than 400 organizations around the world. In addition to

receiving funding, some grantees get help from Microsoft’s data

scientists and access to the company’s computing resources.

In a wide-ranging interview about the program, Joppa described his

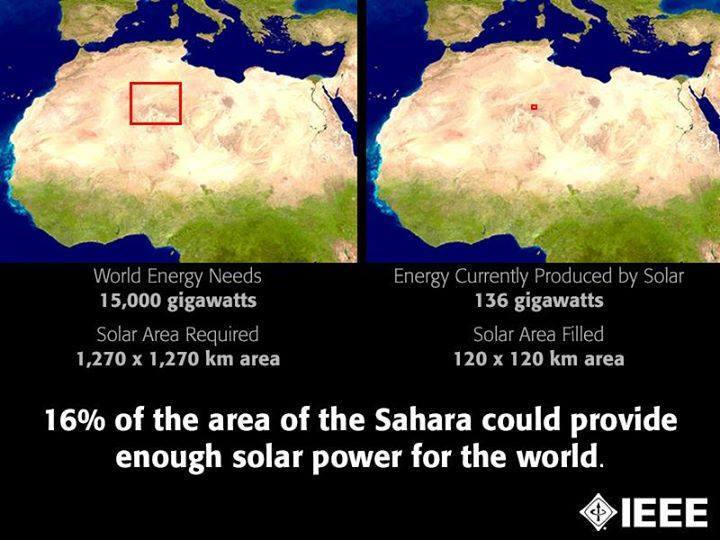

vision of the “ultimate optimization problem”—figuring out which parts

of the planet should be used for farming, cities, wilderness reserves,

energy production, and so on.

Every square meter of land and water on Earth has an infinite number of

possible utility functions. It’s the job of Homo sapiens to describe our

overall objective for the Earth. Then it’s the job of computers to

produce optimization results that are aligned with the human-defined

objective.

I don’t think we’re close at all to being able to do this. I think we’re

closer from a technology perspective—being able to run the model—than we

are from a social perspective—being able to make decisions about what

the objective should be. What do we want to do with the Earth’s surface?

Such questions are increasingly urgent, as climate change has already

begun reshaping our planet and our societies. Global sea and air surface

temperatures have already risen by an average of 1 degree Celsius above

preindustrial levels, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change.

Today, people all around the world participated in a “climate strike,”

with young people leading the charge and demanding a global transition

to renewable energy. On Monday, world leaders will gather in New York

for the United Nations Climate Action Summit, where they’re expected to

present plans to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Joppa says such summit discussions should aim for a truly holistic

solution.

We talk about how to solve climate change. There’s a higher-order

question for society: What climate do we want? What output from nature

do we want and desire? If we could agree on those things, we could put

systems in place for optimizing our environment accordingly. Instead we

have this scattered approach, where we try for local optimization. But

the sum of local optimizations is never a global optimization.

There’s increasing interest in using artificial intelligence to tackle

global environmental problems. New sensing technologies enable

scientists to collect unprecedented amounts of data about the planet and

its denizens, and AI tools are becoming vital for interpreting all that

data.

The 2018 report “Harnessing AI for the Earth,” produced by the World

Economic Forum and the consulting company PwC, discusses ways that AI

can be used to address six of the world’s most pressing environmental

challenges (climate change, biodiversity, and healthy oceans, water

security, clean air, and disaster resilience).

Many of the proposed applications involve better monitoring of human and

natural systems, as well as modeling applications that would enable

better predictions and more efficient use of natural resources.

Joppa says that AI for Earth is taking a two-pronged approach, funding

efforts to collect and interpret vast amounts of data alongside efforts

that use that data to help humans make better decisions. And that’s

where the global optimization engine would really come in handy.

For any location on earth, you should be able to go and ask: What’s

there, how much is there, and how is it changing? And more importantly:

What should be there?

On land, the data is really only interesting for the first few hundred

feet. Whereas in the ocean, the depth dimension is really important.

We need a planet with sensors, with roving agents, with remote sensing.

Otherwise our decisions aren’t going to be any good.

AI for Earth isn’t going to create such an online portal within five

years, Joppa stresses. But he hopes the projects that he’s funding will

contribute to making such a portal possible—eventually.

We’re asking ourselves: What are the fundamental missing layers in the

tech stack that would allow people to build a global optimization

engine? Some of them are clear, some are still opaque to me.

By the end of five years, I’d like to have identified these missing

layers, and have at least one example of each of the components.

Some of the projects that AI for Earth has funded seem to fit that

desire. Examples include SilviaTerra, which used satellite imagery and

AI to create a map of the 92 billion trees in forested areas across the

United States. There’s also OceanMind, a non-profit that detects illegal

fishing and helps marine authorities enforce compliance. Platforms like

Wildbook and iNaturalistenable citizen scientists to upload pictures of

animals and plants, aiding conservation efforts and research on

biodiversity. And FarmBeats aims to enable data-driven agriculture with

low-cost sensors, drones, and cloud services.

It’s not impossible to imagine putting such services together into an

optimization engine that knows everything about the land, the water, and

the creatures who live on planet Earth. Then we’ll just have to tell

that engine what we want to do about it.

IEEE Spectrum

|